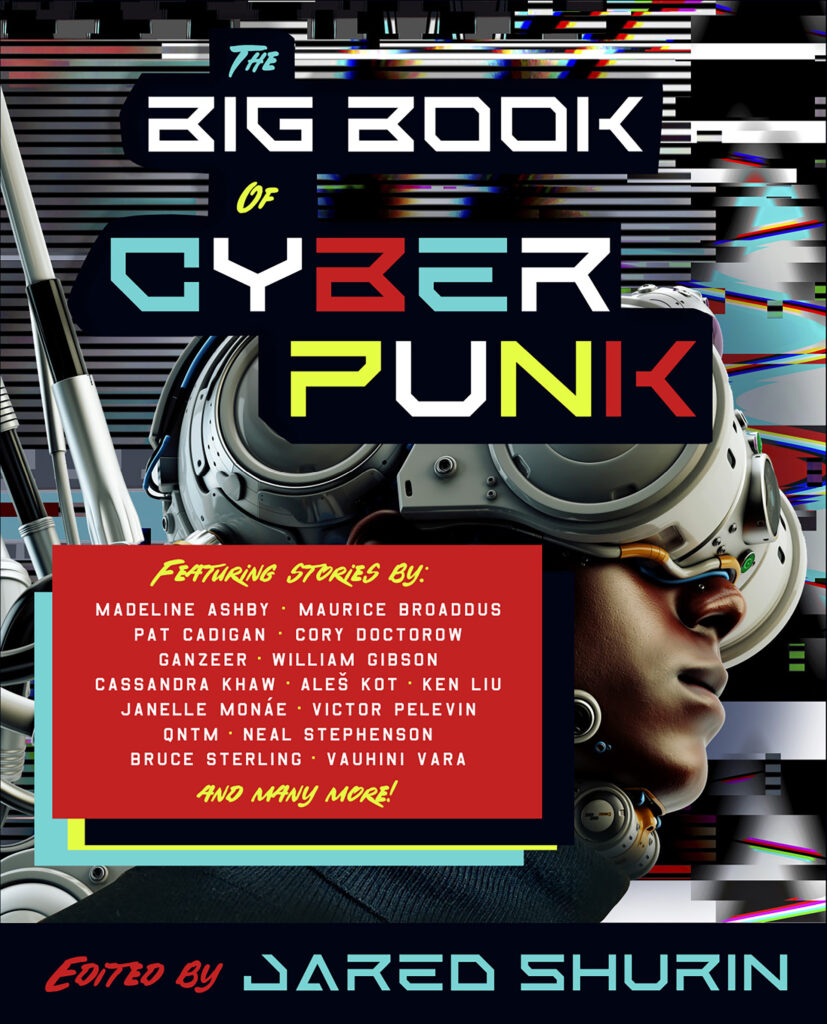

I’ve been working on a really big book of cyberpunk – called, in fact, The Big Book of Cyberpunk. It is a proper cat-squasher: 1,000 pages, containing over a hundred stories. I’ve always been a cyberpunk fan, ever since I was kid. (Fun fact: I wrote my high school ‘term paper’ on Neuromancer. I was that guy.) But a lifetime of cyberpunk reading didn’t really prepare me for the experience of the last few years; that of reading millions and millions of words of the stuff. Magazines, zines, game manuals, clunky hypertext documents, leaflets, scripts, liner notes, manifestos – and, of course, books and books and books.

What I found surprised me. I’ve always known about cyberpunk as a kind of science fiction, but reading back to its origins (and beyond) revealed its strong post-modern roots. It was born as an experimental literary genre, but, as a mode of storytelling, it perfectly captured our uneasy relationship with technology and our anxiety about the future. I also, vaguely, knew that cyberpunk was still kind of a thing, but once I started searching for it, I found it everywhere: sometimes the tracks, sometimes a lost fossil remnant, and very often a living breathing specimen of the genre.

As a result of my immersion, my fandom has reached new and soaring heights. And, like all fans, I’m a little defensive about the genre. The common conceptions of what cyberpunk is (or isn’t) and what qualifies (or doesn’t) aren’t always right. So I’m grateful to the Fantasy Inn for giving me this chance to fact check some assumptions about the genre.

One big caveat, of course: cyberpunk, philosophically, eschews gatekeeping. My answers are neither definitive nor always correct. If you disagree, well, that’s the spirit of cyberpunk: I expect a manifesto and two mixtapes in response!

Cyberpunk is a white dude thing.

The ‘fact’: The original movement was dominated by white guys. In technical terms, it was a sausage party. A lot of the original cyberpunks are still the first names mentioned whenever anyone talks about cyberpunk. Thus: sausage party.

The truth: Part of that ain’t wrong. The original names are bandied about a lot, and that’s because they’re very good. But this also creates the impression that those are the only people in cyberpunk… and that the movement came to a screeching halt in 1987.

Cyberpunk is a genre about rebellion. It is also a literary movement that examines and challenges systems and conventions of all types: political, societal, and even itself. Even as the first wave of cyberpunks were tilting at the big windmills, there were new ‘punks, hot on their heels, tilting at them. My personal favourite is Candas Jane Dorsay’s “[Learning About] Machine Sex” (1988), which is a gloriously scheme-y feminist take on the patriarchy in technology, literature, and speculative fiction.

By the time you get to the present day, cyberpunk – as a literature of rebellion – is, arguably but justifiably, more dominated by traditionally-marginalized voices, and is wonderfully inclusive across all dimensions of diversity; gender, race, class and geography. We can’t (and shouldn’t) forget about the incredible work of William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, but cyberpunk in 2023 owes just as much to Janelle Monáe and the Wachowskis.

It is also worth noting that, even in the very early days, cyberpunk wasn’t exclusively white and male – those original figures also deserve much more attention.. Pat Cadigan, Melissa Scott, and Lisa Mason are the obvious examples, as well as Max Headroom’s AJ Jenkel. Misha was right there with them. Nisi Shawl’s first published story was an early cyberpunk piece. Samuel R Delany was, as in all things speculative, a key figure. Ellen Datlow was the invisible hand behind the formation of the genre, publishing many of the most important pieces during her glorious reign over Omni.

Finally: cyberpunk went very global, very quickly. Writers from all over the world were taking part in this exciting new mode of storytelling from its very first days. Publishing being publishing, a lot of the non-Anglophone contributions have been overlooked. This is something I’m glad to correct in The Big Book, with some of the OG global cyberpunk classics getting their first English publication.

Verdict: FALSE

Cyberpunk is dead.

The ‘fact’: Cyberpunk died with the 1980s – if not earlier. It was a flash in the pan genre that railed against the burgeoning technocratic society, before being subsumed by its own success. You can’t punk when you go mainstream, can you? Worse: it is hard to write scarily predictive speculative fiction when scary reality is outpacing you. A lot of the people most involved in the movement have declared it over and done, some saying it barely outlived its first few years.

The truth: It is hard to argue with our cyberpunk reality. It is equally obvious that many of cyberpunk’s dominant tropes – from AI, cyberspace, virtual worlds – have permeated every genre. There are romances in virtual worlds, android superheroes, portal fantasies to video games… meanwhile, literary novels deal with cyberbullying, online identity, nefarious corporations, and robot companions. Cyberpunk is less dominant than diffused. It is hard to point out what’s specifically ‘cyberpunk’ if everything is.

But… it still lives. As a core set of introspective, revolutionary themes, with its torch carried by a new generation, from Erica Satifka to Oliver Langmead, Ganzeer to Lavanya Lashminarayn. There’s an active core of creators – across all media – applying cyberpunk’s unique fusion of speculation and post-modernism to the problems we face today, in 2023.

Second, as an overwhelming aesthetic – a visual way of representing a certain future – cyberpunk is everywhere, across all media channels. It is in music, fashion, movies, television and games. Is Vision and the Scarlet Witch the same cyberpunk as found in Mirrorshades? What about Severance? Or the recent Fortnite expansion? Probably not what Sterling was writing about in Cheap Truth, but it is something, and it is very much alive.

Has it evolved? True. Has it changed? True. Has it lost some of its original purpose? Sometimes. But is it dead…

Verdict: FALSE (And I have a lot of stories to prove it)

Cyberpunk is science fiction noir.

The fact: ‘Noir’ is that genre where people stand outside in the rain, drinking heavily while molesting the women around them. Cyberpunk is that, but with neon lights. And sometimes the women are androids! ERGO, cyberpunk is science fiction noir.

The truth: This gets my goat on so many levels. A whole pyramid of goats, all gotten. A TOWERING BABEL OF GOATS. I think it stems from two small, but fairly fundamental, misunderstandings. Those is, what is ‘noir’ and also what is ‘cyberpunk’. It is pretty hard to equate the two when you’ve got them both wrong. This issue is further compounded by the fact that people get them wrong in the same way: they confuse the aesthetic with the genre. Just because someone is wearing a fedora doesn’t make a book noir (you think this rant is heated? Ask me about the Dresden Files), any more than sunglasses makes a book cyberpunk.

To be fair, the issue is complex, because there are works that sit, arguably, both genres. Richard Paul Russo’s Destroying Angel is an actual-for-real noir detective novel set in a cyberpunk San Francisco. Lavie Tidhar’s A Man Lies Dreaming is also a noir detective novel that connects with cyberpunk’s gonzo post-modern tradition. And you may be familiar with Blade Runner. However, you also have works that are, say, noir and Western, and you don’t have people running around saying that all Westerns are historical noir, or cowboy stories are noir with bigger hats.

There are some thematic similarities, but this is coincidence, not a deeper connection. Noir, for example, is typified by a claustrophobic atmosphere. Cyberpunk stories can often have the vibe, as a result of feeling an oppressive or overbearing system. Janelle Monae and Alaya Dawn Johnson’s excellent “The Memory Librarian” is about loneliness and isolation. It even has a kind of detective! It is not, by any sense of the imagination, noir. Both genres generally (but not exclusively) take place in cities: in noir because it adds weight to that sense of isolation; in cyberpunk because that’s generally where the most technology is found. But then, so do the Kate Daniels books, and most billionaire romances. Urban density alone doth not noir make.

Now, a couple pints in me, and I could probably put together a compelling argument that both cyberpunk and noir stem from the same root cause – disillusionment with conventional definitions of success. I don’t think that’s right, but it’d kill time until someone asks the panel another, more interesting question. But, sadly, when people are saying ‘cyberpunk is science fiction noir’, they’re not really talking about the themes, they mean it is wet, dark and grumpy. Thanks, Blade Runner. Thanks a lot.

Verdict: FALSE

Cyberpunk is dystopian.

The ‘fact’: Cyberpunk stories feature cruel corporate overlords, feckless sellout governments, and robust systemic inequality. Against this grim backdrop, we have a lone, morally ambiguous actor who operates solely out of self-preservation. Nobility is futile, hope is dead, enjoy your McMuskin. (In 2030, Elon buys McDonald’s, obviously.)

The truth: Cyberpunk settings are often pretty bleak. Which is why people like to use ‘cyberpunk’ as a synonym for ‘dystopian’ when they’re told that pensioners should be Uber drivers, or we can ignore climate change in favour of steadily raising our own body temperature. Those are a) real, b) dystopian and c) cyberpunk af.

However, dystopias are static. They’ve bottomed out. What you see is what you get, unless it somehow gets even worse. Whereas cyberpunk is, as mentioned above, a literature of rebellion. It is predicated on the need for challenge; dynamism. Whether or not the revolution is successful, the act of rebellion is meaningful, and often has its own, discrete impact. Michael Moss’s “Keep Portland Wired” is a great example of this, as is EJ Swift’s “Alligator Heap”, and, of course, Lavanya Lashminarayn’s The Ten Percent Thief.

This also means Cyberpunk, is – and you may want to put your own drink down for this – very often hopeful. On the most basic level, cyberpunk works are about a belief in change, and the irrepressible elements of human nature. Again going back to Neuromancer, the world shifts – in a small, but tangible – way due to the actions of our heroes. Case and Molly wind up as better people. They help others and free Wintermute. (Er, spoilers.). No one is mistaking cyberpunk for epic fantasy, but it is not a hope-free genre: it is a genre about challenge and change, and never, ever stasis.

Cyberpunk is about exploring the probabilities (not possibilities) of technology, and the impact on human lives. However critical or negative the path may be, there’s still very often the opportunity for creativity, resistance, and hope.

Verdict: FALSE.

Cyberpunk can’t contain magic.

The ‘fact’: Mate, cyberpunk is basically near-future science fiction. We don’t have wizards and shit, as that’d ruin the realism. And Shadowrun is for fake geeks.

The truth: First, Shadowrun is awesome, and modern cyberpunk owes a lot to it. There are Shadowrun stories in The Big Book of Cyberpunk (possibly the first ‘tie-in’ fiction in the series?). One of them, Jean Rabe’s “Better Than”, is a stone-cold classic about identity and transhumanism. It requires no knowledge of the setting, and there’s no ‘clatter of dice’ about it – but it uses the rich Shadowrun world to its best effect, and is absolutely soul-destroying in its power.

Second, cyberpunk has always embraced the weird and unfathomable, thanks in no small part to its post-modern roots. Robert Anton Wilson was part of the original crew, and anything involving the Discordians was going to go strange places – but his thinking (and his editorial work) had a huge influence on the genre. The Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) took this to another level in the 1990s, fusing cyberpunk and occultism to create their own unique subspecies of ‘theory-fiction’. Phil Hine cites ‘cybernetic’ thinking in his primers on Chaos Magic. These are an extreme example, but shows how cyberpunk both permits – and often encourages – more fantastic elements.

Cyberpunk, from the start, has been about hacking all the systems: technological, human, and – ultimately – metaphysical. If you flip through the core ‘canon’, that is, Mondo 2000, you’ll find as much wordage about expanded consciousness as expanded RAM.

There’s a strong thread of spirituality woven through the genre. Russell Blackford’s “Glass Reptile Breakout” is about transhumanism and the soul; Misha’s “Speed” is about finding god – and Lisa Mason’s “Arachne” is about god finding you. Gerardo Horacio Porcayo’s “Ripped Images, Rusted Dreams” takes it a step further, and is about running away (VERY QUICKLY) from god. Harry Polkinhorn’s “Consumimur Igni” emphasises how going online is a type of ecstatic experience. Again to cite Neuromancer – but it contains a lengthy and powerful discussion about transcendence, with Case having somewhat otherworldly, mystical encounters. Everyone remembers the ninja assassin, but conveniently forgets the loa.

Verdict: FALSE

If you’re intrigued by any of these references – or just want to escape into some dystopian neo-noir in a rain slicked neon landscape – please do pick up The Big Book of Cyberpunk (out this month from Vintage). You might need to clear some shelf-space first.

-Jared Shurin

2 thoughts on “Cyberpunk: The Truth Behind the Shades”