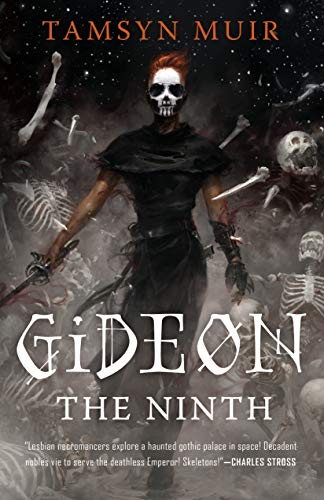

Today we have with us Tamsyn Muir, author of the upcoming novel from Tor.com, Gideon the Ninth. We discussed the appeal of horror, what it takes to make a kick-ass necromantic magic system, and her upcoming projects.

Hi Tamsyn! First of all, how are you and how have you been?

Hey, thanks for asking!

Right now I’m pretty overwhelmed, which I say not as a pity-me plea but as a corrective to the idea that getting your novel published is an unending rollercoaster of nice excitements. As of writing Gideon the Ninth is a few weeks from publication, and I love the idea that in a very short time I can share Gideon with anyone who wants to read it. Nonetheless, it’s a few weeks until Gideon’s out, and I’m ready to set up a private station in the Antarctic, and die there.

I’m trying to run a steady diet of not reading any reviews unless they are physically handed to me by my publicist, but the nicest review in the world still short-circuits me, because the pathways of my brain were put in by some cowboy without a license. I know that people are very ready to say a book is over-hyped. As a Kiwi, I myself was ready to say my book was over-hyped when Tor.com made it clear that it would be put in bookstores and not dumped by the dozens in the nearest sanitation pond.

For instance, the review of Gideon the Ninth within The Fantasy Inn’s very e-pages gave me a brief flush of real pleasure, and then I immediately went back to preparing my apology speech.

Could you tell us a bit about yourself, your journey, and how you became Tamsyn Muir: teacher, writer, and bone enthusiast?

Tamsyn Muir was constructed from some very dubious class kits, but nonetheless is still a contender for end-game raiding.

I’ve been writing since I was very young—an early memory is constructing some overheated Samurai Pizza Cats fanfiction on Post-Its—and fantasy, science fiction and horror books and games helped me get through my childhood intact. In fact, I am afraid that I spent more time on the writing, books and games than pretty much anything else: I was not very good at schoolwork, nor was I happy at school, so I bumbled along and eventually was put in a special class where they told us we should prepare for a life in the army, the tourism industry, or if we were very lucky, wiping down the tools in specialised labs. All of this was nonsense, naturally, because I had flat feet, none of the charisma or drive needed for the tourism industry, and certainly none of the reliability needed to wipe anything down. I left school at sixteen having scraped up the very lowest mark needed to go to uni with, went to uni to do Classics (??) and English , and… immediately dropped out. I spent the next years working retail, and then somebody kind told me that kids DID respond well to teachers who understood that school could be pretty hard, actually, and I went to get my B.Ed.

I think anyone who really wants to understand fantasy, science-fiction and horror should just go teach secondary or primary English for a few years. I taught both English and English as a Secondary Language, which was delightful. Teaching kids how to write forces you to examine your own writing in a big way. Reading the writing of talented, interesting, funny kids is also a great lesson in how you only have a few more years on this earth before the writing industry is taken over by the kind of people I was teaching. Oh my God, they were so good. If only I’d been a little more unscrupulous I would’ve tried to push them into doing law or medicine or something so they’d be too busy to write.

The only explanation for the bones is that I read a lot of Usborne books and there was always one page where they showed you a diagram of a grave with a label like, “And this is where the body was buried,” which threw me into ecstasies of panic. I can’t stand how scared I am by bones, mummies, bog bodies, and looking at pictures of cryogenic labs, but I also can’t stand how much I love them. I played Sweet Home for the NES, which is just pixellated skeletons spread everywhere, and I screamed.

What were your most important takeaways from attending Clarion? And what have you learned in your years of writing since then that you wish you’d known at the start?

I attended Clarion in 2010, just after I’d graduated my Bachelor of Education and was about to get paid to teach for the first time. I think the most important thing it did for me is not something I can easily replicate for those of you at home, because it validated me as a writer. I’d never thought of myself as a capital W writer. I had amused myself previously by writing fanfiction where Final Fantasy characters contracted diseases. Being at Clarion let me begin to take myself seriously, the most important lesson of all. It also taught me about story structure, and let me transition from Final Fantasy diseases by forcing me to concentrate entirely on plot and not on character—I would tell anyone wondering how to transition from fanfic to original to just spend a year writing short fiction—and to read my own work critically.

None of the lessons I know now I could’ve known at the start, because they’re all lessons of time and experience. The nice thing about my younger writer self was that she’d already learned the best lesson: to have fun with this thing. I spent twenty-seven years having fun, and it was the best possible education I ever could’ve had.

You’ve said before in and interview with Nightmare Magazine that you love cannibalism for its visceral physicality and innate spirituality. Can you talk a bit about what draws you to horror as a genre?

Oh, horror is wonderful. I like to think that science fiction and fantasy are where we examine the boundaries of our existence and that horror is where we examine the boundaries of our Id. Unlike the other two genres, horror is where I get obsessed with the technicals. I love watching and reading and playing a good horror story and watching the creator do something and being all, “God! That was incredible! How can I backwards-engineer that?” I’ve never gotten over that skin-crawling creepy feeling from my earliest days of reading Stephen King at way too young an age, and I love it—I love the science of trying to conjure specific meat reactions in my reader. I guess it’s the same reason someone might really love erotica as a genre, except it seems to me there are a minimum of skeletons in erotica. I hope nobody corrects me here, I want to go on living with that as my understanding.

Fear is a prominent part of the horror genre. On that note, what scares you?

Cryogenic freezing of the body, especially the process and keeping thereof. Chambers where the body is buried. Mice.

Translated, I guess you could say that I’m deeply afraid of transgressive burial practices and putrefaction/physical despoil. If you go deeper it may simply be linked back to, as a child, digging up graves in A Link To The Past and having ghosts fly out and bite me.

Several of your short stories are influenced by Lovecraft’s work, most notably The Deepwater Bride and The Woman in the Hill. What about Lovecraftian fiction in particular attracted you despite the author’s personal views?

One think I think Lovecraft does extremely well—which may, alas, also very well tie in to the “grotesque personal views” thing—is write anxiety. It’s no secret that Lovecraft was under an immense burden of stress, and I feel this comes through pretty loud and clear in his work: he writes the slow—or at times extremely quick—slide from okay to AI! AI! in a way I personally find pretty authentic, and his characters’ jittering, clench-jawed sufferings in the face of unspeakable terror is fresh and new every time I open a Lovecraft story. I don’t think that his cosmology or his pantheon of unspeakable beasts would still live in the public imagination were it not for the fact that in a Lovecraft story, the fear is always real. As a horror author I’m desperate to copy that technically.

Unlike Lovecraft, your stories prominently feature queer women. What impact are you hoping to achieve by featuring characters in Lovecraftian fiction that Lovecraft would have avoided?

I’m just writing to amuse myself, as per usual. I wish I could say that I wanted to inspire a new generation of writers to play around in Lovecraft’s hideous geometries without Howard’s more tedious hideous geometries, but that would be me covering up my main motivation, which is that I loved Lovecraft’s cosmology and I would’ve loved it more had Asenath Waite skateboarded from place to place. Okay, that’s not quite true either—Lovecraft doesn’t work if you don’t take the crawling evil and transmissive rot totally seriously—but so much of Lovecraft is so good, and all of his guys are the same guy, and I want to fundamentally prove my pet theory that Lovecraft is improved rather than ruined if character and comedy come into it. And because it is me, those guys are going to be grizzled, ruggedly sensible turn-of-the-century Auckland widows—like in my short story The Woman in the Hill—or self-important, precociously intelligent teenage girls, like in my novelette The Deepwater Bride.

I hope that’s inspirational, despite my first motivation being me. One of the most meaningful things that ever happened for me in the Lovecraft universe was when I played Daughter of Serpents, a 1992 PC game. I played as a female Egyptologist, and I’m sure it was easy enough to code in and it had no bearing on the plot, but it was so electrifying to finally be a Lovecraftian heroine. I hope one day I will be somebody’s Daughter of Serpents (I just wanted to write that as a sentence).

Your debut novel, Gideon the Ninth, releases in less than a month. What can you tell us about it?

It’s the story of a swordswoman who’s unwillingly signed up to help the person she hates the most in all the world become God’s immortal bodyguard. When it turns out that the path to becoming God’s immortal bodyguard is paved with LOTS of murder, who can she trust when the (bone) chips are down?

Gideon the Ninth is fundamentally the story of Gideon Nav, whose story blurs the boundaries of murder mystery, psychological thriller, girl-leaves-home Bildungsroman, and Sports Story (so long as for “sports” you read “swords”). She lives in the Nine Houses, a necromantic civilization led by the Emperor Undying, who also serves as their immortal God in his ten thousandth year of rule. Gideon’s a brash wannabe soldier who’s desperate to do her own equivalent of travelling to Troy and winning Achillean renown: she’s good at one thing—the sword—and she’s grown up in the one House who don‘t care much about being good with swords. By an accident of birth, she’s been fostered in the Ninth House, which is basically a remote retirement home on the edge of the planetary system where there are three members left under fifty. These are the House swordsman, Ortus Nigenad, a guy who unfortunately hates swords; the House heir Harrowhark Nonagesimus, who is an incredibly talented necromancer and the bane of Gideon’s existence; and Gideon Nav, who loves swords but is the curse of her House.

When this awful set-up gets complicated by the Emperor’s call for the heirs to his Houses to attempt to ascend to a higher plane of existence, it’s not a spoiler to say that Harrowhark decides immortality is actually going to require the help of someone who hates her and who she really hates right back.

On a more meta level, Gideon the Ninth is about a baby-butch lesbian who has to pick between duty and glory and made the decision long ago that it was going to be glory. The conversation about duty versus glory is so live and dangerous to me.

One thing I wondered while reading Gideon the Ninth was: why set the series in space? It’s not every day that necromancers board spaceships to travel the galaxy.

I think this ties into the previous question for me. What’s Gideon the Ninth about? On an even more meta level, the whole trilogy is about me setting up a huge worldbuilding mystery, because I come from the video-game tradition where the entire point of playing is to glean whatever tiny scraps you can and put them into your own semblance of order. I look at worldbuilding as a resource I am hoarding. Put these pieces together, I cackle. This isn’t how a novel works, my audience reminds me.

Why the hell is the series in space? I mean, for one thing because I can’t get enough of science fantasy and I think that necromancers in space is the peanut butter meets chocolate matchmake where other people think it’s peanut butter meets pickles, but there’s more to it than that. It’s part of a bigger story I’m trying to tell about galactic revenge, and cosmic chickens coming home to roost: the last book of the trilogy is called Alecto the Ninth, and Alecto, famously one of the Furies, is a pretty big hint about the series’ throughline.

Also, I was born in 1985. I watched Star Wars as an infant. Swords and space are in my blood, man.

What were some of the most difficult challenges you faced transitioning from short fiction to writing a novel? Similarly, what was it like to have to design a universe from scratch?

I cut my teeth writing very long fanfics, so it was a more difficult transition to short fiction in the first place. I found that transition helped enormously when writing a novel, because I didn’t write Gideon the Ninth for the characters—I wrote it entirely for the structure. I wanted to tell a very specific story, and I needed everything to serve that story. Once you’ve got the structure you’ve got the beats, and once you’ve got the beats you’ve got the acts and chapters, and once you’ve got the chapters you’ve got the beats in the chapters, and so on.

I think the biggest difficulty was honestly how much gets left on the cutting-room floor. You’ve got this very specific idea for how everything’s going to look and be executed, and it doesn’t survive to be written—it’s not even that you write it and you have to take it out, it’s that on contact you realise that it isn’t going to work. There was a time before I started Gideon where I was like, “Oh yeah, this is structured like a school story, this is almost Angela Brazil.” I started writing and knew that this was not a school story. It was not Angela Brazil. I make fun of myself before the end of Act One where most of the characters assume they are about to enter into a school story, and the mentor character, Teacher, basically says: “You thought this was going to be something out of Enid Blyton?? Piss off.”

The universe came into being pretty much fully-formed. I looked at the one page of notes I wrote on an airplane before I started writing Gideon, and the universe is exactly the same barring two things: suffering from extreme New Zealand jetlag I thought that calling the Emperor “the Necroi” was really clever until my beloved spouse said it out loud and laughed at me. There is also a very wonderful note that just says, “Gideon is a fireman or a policeman,” which goes to show that we are living in the wrong universe, because Gideon is not a fireman or a policeman. I told that to someone the other day and they just said, “You were just trying to make Gideon all the things you can be on a sexy calendar.” In hindsight, yes.

Your version of necromancy is a good deal more complex than simply raising the dead. How did you approach building your magic system?

I had two needs straight-up that I had to fulfill:

- I needed my necromancy magic system to be aggressive, and not rely entirely on speaking with the dead or even raising self-actuated undead. This isn’t a zombie story, or Frankenstein. I wanted to center my system around things that were not “the unholy costs of raising… the dead.”

- But I still needed costs. I wanted a magic system with very specific things you could and couldn’t do. I wanted it in most cases to not be about reagents, which a lot of stories about necromancy focus on — it’s not that I don’t love material-based magical systems, but it becomes a story about scarcity and resource pretty quickly, and I needed this magic to be focused on a person’s talent and scholarship. The necromancy in my story, although it is a genetic and inherent talent, has to be nurtured and cultivated. I’m not sure why I wrote a system where my wizards get good after forty years alone in a tower, because I hate homework and I wasn’t good at school.

I had worked out pretty early on what was special about the God-Emperor and what was special about his Lyctors, the ultimate necromancers of the Nine Houses, and from there it was pretty easy. I came up with my two main elements, thalergy and thanergy (which started off as phthinergy until I just thought it sounded too much like an antihistamine), life energy and death energy; my magic runs off very local and specific concerns rather than ley lines or the Force, necromancers in my universe have to have specific sources of death energy around them before they can do anything. You can’t do necromancy in space. You can’t even do necromancy on planets that haven’t been tampered with in the way that the Nine Houses planets have been tampered with, which is a bit of a spoiler for the concerns of Harrow the Ninth but never mind. These strictures worked great for me, because that’s an immediate story hook: how do different necromancers produce thanergy? I love specific magical skill sets, so that already let me have my Ninth House necromancers, who can wring and reignite old thanergy very effectively and therefore are the masters of the skeleton. It let me have my Sixth House necromancers, who are psychometrists and very good at finding thalergetic and thanergetic traces of magic left on things. It let me have the Second House, whose necromancers convert thalergy very violently to thanergy, mainly from Second House swordspeople chopping people up. And so on and so forth.

Identifying need is the most important thing for me. I’m very relieved that I busted my butt getting all this stuff sorted before Harrow the Ninth, which is just necromantic theory all the way down. It’s also fight scenes, I promise.

Your book has both murderous eldritch horrors and an irreverent narrator who doesn’t always take things seriously. How do you strike a balance between the two?

I looked at who did it first and decided it was Joseph Heller. Not many people would put Catch-22 in the same breath as Gideon the Ninth, but Heller juxtaposes the horrors of World War II with John Yossarian—Yossarian is one of my favourite characters of all time, by the way—who does not take things seriously while at the same time taking things more seriously than anyone in the book. His DNA, funnelled through my inexpert hands, definitely ended up in Gideon. I just think it’s a source of endless comedy and endless horror, and I think comedy makes horror sharper and horror makes comedy funnier.

The only balance to be struck is in what real human beings say or do or how they react in the face of terrible things. A lot of the cruel humour in the book actually comes from the text rather than from Gideon herself. Gideon’s a Kiwi heroine when it comes down to it: she tries to downplay terrible situations by being offhand. Or sometimes she just says FUCK really loudly as she falls down some stairs. I like to think she never has a reaction in the book that’s unrealistic: she often blusters, or tries to cover how she’s feeling, or doesn’t know what to say and says something stupid, but—she’s just human, and she’s not trying to be anything different. It’s Harrow who is trying to be less than human, and react to things in a less human way; Harrow acts as a natural foil and balance for Gideon narratively.

I’ve heard the sequel, Harrow the Ninth, is already written and well on its way to publication.

Yes, thank God!!! Very weird, though, because I’m already impatient for people to read Harrow and Gideon isn’t even out.

Have you started writing book three yet? If so, how’s that going?

No, I’m scheduled to start writing Alecto the Ninth in October. I’m really looking forward to starting. Harrow was agony and ecstasy, and I’m glad that you can only ever start writing your second book the once, as it were. I want to write Alecto as swiftly as possible, because Harrow really benefited from nobody having read Gideon—I could just write the book in a beautiful vacuum with only my own expectations to contend with. I want to start and finish Alecto with my hands over my ears about how people feel about Harrow, let alone Gideon. This is impossible as, said before, I’m already getting feedback, but I’m going to try to be really good and enter my space chamber and ignore everything until I am safe.

Are there any other writing projects you’re dying to dig into once The Ninth House is complete?

Yes, and I wish I could talk about them more, but a lot of them are secret! I can say that I’m doing a novella with Subterranean Press. It is about a princess in a tower who has a very bad time. It’s like if Noel Streatfield met Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet met a very bad run in Rimworld. I’m doing my first game-writing project too, which is great fun but such a learning curve.

Have you read/watched/played anything recently that you really enjoyed?

As per usual, I’m playing a lot of video games. I just finished Hypnospace Outlaw from Tendershoot, which is a love letter to 1990s Geocities webpages and is just some of the cleverest game storytelling out there at the moment. I’m going to be yelling about it a lot once the Nebula nominations come up. I’m continuing to play Cultist Simulator from Weather Factory; I’m so bad at it, but I love it so much, and I also think it is doing enormously clever things with video game storytelling and mechanics. I’ve survived really far on my latest run because I keep having enormous luck in kidnapping all the detectives who come after my budding cult leader, and they keep dying in prison, so I have this never-ending carousel supply of corpses, which is very useful in Cultist Simulator.

I’m re-reading The Unspoken Name by A.K. Larkwood—really top epic fantasy that’ll be out next year with a heroine who’s an orc ex-priestess who’s found herself becoming a villain’s sidekick, and if anyone liked Gideon being good with a sword and awkward with the ladies they’ll love Csorwe, who is immeasurably more with-it than Gideon but has similar taste in chicks. Larkwood’s writing is out of this world. And in the realms of not fantasy at all I’m reading Weatherland by Alexandra Harris, which is an examination of how the English weather has changed in the creative imagination over time. It is absolutely incredible and lovely. I frankly think anyone with an interest in worldbuilding ought to read it.

I want to close on a quote that stood out to me in the article you wrote for Tor.com about Return of the Obra Dinn:

the awards should be given, in my mind, for things that make us recognise what science fiction and fantasy can do. They should be given for those things that make people say, “Yes, more of that.”

What do you hope people will be saying “Yes, more of that” about after reading Gideon the Ninth?

It’s not something I did deliberately—I’d say I did it out of ignorance—but I want people to realise there are no boundaries. I wrote a murder mystery science-fantasy set in the middle of a will-they won’t-they rapprochement between two human beings who have been terribly hurt by the world. At times it’s structured like a romance novel—then like a horror story—then like a coming-of-age story—then a murder mystery. It’s SFF by way of Final Fantasy, Phoenix Wright and Peter Høeg. I’m sure plenty of people will put it down saying “Wow, if we have to have more of that, then not by Tamsyn Muir, whom I hope goes back to any other career,” but what I want them to say is—“Wait, you can do that in science fiction and fantasy?? Can I do that? I thought I wouldn’t be taken seriously.”

I also want to release people from having to take their universe entirely seriously, if they don’t want to. I take my story very seriously, but I’m anachronistic, a lot. My narration includes useless memes and jokes for the reader that nobody in my universe would get. I’ve driven my lovely and talented copyeditors wild (“How can you justify Gideon saying ‘that’s bananas’ when she’s never eaten a banana”) and my editor is now in one long exchange of hostages with me where I can keep some references and have to lose others.

Science fiction and fantasy reflects ourselves, our anxieties, our joys. It’s okay if your joy growing up was all contained in that one Choose Your Own Adventure book where you journey into the center of the planet and if you gather diamonds you die by being gassed by a mountain. Reflect everything you are in your work, not just the things you think are fit for public consumption. Gideon the Ninth gave me the strength to write Harrow the Ninth, which is the most personal book I have ever written. Now that I think about it, Harrow is the second book I’ve ever written, so that’s not as deep a line as I’d hoped it would be.

Thanks for visiting the Inn and chatting with us!

It’s been an honour.

About Tamsyn Muir

Tamsyn Muir is a horror, fantasy and sci-fi author whose short fiction has been nominated for the Nebula Award, the Shirley Jackson Award, the World Fantasy Award and the Eugie Foster Memorial Award. A Kiwi, she has spent most of her life in Howick, New Zealand, with time living in Waiuku and central Wellington. She currently lives and works in Oxford, in the United Kingdom. Gideon the Ninth is her first novel.

Follow her on Tumblr at tazmuir.tumblr.com and on Twitter @tazmuir. Her website is tamsynmuir.com.

I love Tamsyn so much! Gideon the Ninth is my favorite book of the year, and it was so wonderful to get insight into her writing and thought process. Thank you so much for putting this together, it was a pleasure to read!