A term that has picked up steam in recent years is “cultural appropriation”. In my rough understanding, this denotes someone using concepts, ideas, or elements from another culture for their own purposes, usually with little regard or consideration. At best, this is deeply insensitive; at worst, it perpetuates racist stereotypes. This idea has been studied in academia for a while; already back in 1978, Edward W. Said published his influential work, Orientalism. In this book, he examines how European culture has long been drawing upon imagery from the Near and Far Orient (northern Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia) for its own purposes. Usually, through art and literature, the Orient was turned into an exotic place, primitive in some ways but alluring in other – a place of adventure and self-discovery for the Europeans, who ventured there. The purpose was never to actually investigate or understand these areas, but simply to act as an Other, allowing Europeans to bolster their own image, defend imperialist policies, etc.

This pattern has been pervasive in Western art for centuries, making it difficult for contemporary, Western writers to avoid, should they be interested in exploring stories set in non-Western locales. The same holds true for fantasy authors; while we can take liberties with how we construct our worlds and their cultures, we are still responsible for not only the inspiration we take from real cultures, but also how we use that inspiration and any implications born of that usage. I can think of two major pitfalls for any writer of fantasy or historical fiction taking place in non-Western settings, especially those that have often suffered under Orientalistic portrayal. The first pitfall is when the writer simply grabs ideas, history, characters, events, names and terms, and sometimes even clothing without regard for their cultural significance and context. By transplanting these elements out of their context, the writer comes close to making a mockery of their meaning and importance, indirectly also mocking those people to whom these elements are important.

A simple example of getting this wrong from TV would be Vikings. In the mythology, the name “Lothbrok” is an epithet given to Ragnar after he slays a dragon while wearing furry breeches (it’s a long story) – it makes no sense that he would be called this in the TV show unless the same specific story played out. The name would definitely not be applied to his wife or children – there is no such thing as “The Lothbroks”. We don’t refer to her as “Roxana Great”, just because she married a certain Alexander. I am nit-picking here, and I don’t have strong feelings about Vikings one way or the other, but it is a good example of how writing a culture you don’t understand can become farcical. The second pitfall is arguably worse. It is when the narrative itself becomes a façade for promoting stereotypes; as mentioned, these are usually racist in nature. The Western traveller (or equivalent in fantasy literature) explores the Oriental lands, reinforcing the stereotypes already in play. Another example, this time from cinema, will serve to show how.

In Avatar (the one with the blue cats, not the air getting bent), the protagonist Sully is sent to colonise another planet. He is white, male, and (former) military, the hat-trick of imperialism. He encounters the native Na’vi, who are technologically inferior but spiritually enlightened (a staple of Orientalism). We see Sully prove himself superior to the natives when he is the only person who can tame the Last Shadow, a near-mythical creature. He leads the Na’vi into war as their natural leader, and he ends up with the princess of the clan as his trophy wife. This narrative has no interest in the Na’vi, who are reduced to minor characters, and they are only present to serve some purpose or facet in Sully’s story. How to avoid these pitfalls? This was a question I was forced to resolve when I began writing my upcoming book, The Prince of Cats. Inspired by primarily Arab culture, I was a prime candidate for repeating the mistakes of Orientalism. This was my solution.

The first pitfall must be avoided by comprehensive research. Nearly every populated area in this world has been studied, whether we are talking history or culture. If you are going to use terms and names, make sure you fully understand their significance; especially, make sure when you should refrain from using them altogether. The culture that you’re being inspired by should be approached with respect. A minor example: knowing the high regard that Arab culture places on poetry, I wanted to mirror that in my inspired culture. As a result, it is common to find epigrams with poetry inscribed on the entrance to buildings, the children are taught to memorise and recite poetry in the madrasa, and on occasion, characters will use proverbs and sayings made by poets in their speech. The second pitfall requires strong awareness and consideration of the story you are writing. With regards to the main character – is there only one, and is it an outsider arriving to the culture you’re portraying? Are they presented as superior, even at tasks or feats that the local characters are trained and experienced at? What about minor characters – are they simply intended to service the storyline of the outsider protagonist? Are they presented as primitive and inferior? If the answer to one or more of these questions is “yes”, that is a good reason to re-examine your narrative.

You should not rely entirely on your own research and analysis, though. If you have blind spots, you need someone more knowledgeable to point them out. To this end, you should recruit someone who is actually from the culture you’re taking your inspiration from, to consult with. I was fortunate enough to have a reader from Yemen before I began writing my story, who was an immense help with my foray into Classical Arabic, ensuring that my usage of Arabic words was done correctly (shout-out to Hisham!). When the first draft was done, he also did what could be called a sensitivity read, double-checking my use of words, terms, names etc. and pointing out any potential issues. Will this ensure nothing in your book can be considered problematic? I don’t think such a guarantee exists. Should you end up erring somewhere, there is little to do but acknowledge the fact and offer up your apologies. But following these guidelines will at least take you a lot further than the alternative. Closing your eyes to the pitfalls of Orientalism will only make you stumble into them.

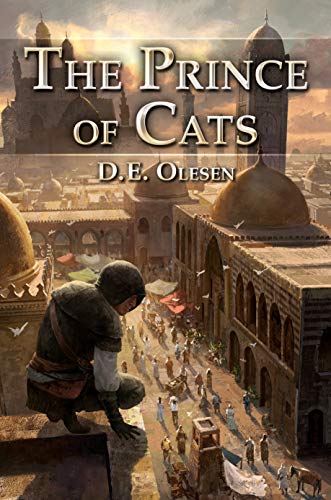

The Prince of Cats

To stay alive, Jawad must succeed where all others have failed: he must catch the Prince of Cats. More legend than man, the Prince is draped in rumours. He can steal the silver teeth from your mouth in the blink of a smile. He is a ghost to walls and vaults, he laughs at locks, and Jawad must capture him before powerful people lose their patience and send the young rogue to the scaffold.

Ever the opportunist, Jawad begins his hunt while carrying out his own schemes. He pits the factions of the city against each other, lining his own pockets in the process and using the Prince as a scapegoat. This is made easy as nobody knows when or where the Prince will strike, or even why.

As plots collide, Jawad finds himself pressured from all sides. Aristocrats, cutthroats, and the Prince himself is breathing down his neck. Unless Jawad wants a knife in his back or an appointment with the executioner, he must answer three questions: Who is the Prince of Cats, what is his true purpose, and how can he be stopped?

The Prince of Cats releases on November 26th

Pre-order The Prince of Cats on Amazon, or at Apple, Kobo, and other stores.

It’s ok regarding lothbrok. That’s how names are created honestly. It’s sikander e azam spawing sikander babies. Even Sinbad is a play on a phrase someone came up with long ago. Creating a character called Ragnar Lothbrok seems fitting and a tip of the hat.

I agree with some of your main points though, just think you should replace this example with something better.